Multilingual POS Tagging & Context-Aware Autocorrection

Building a robust, hybrid NLP pipeline for real-world language understanding across English, Japanese, and Bulgarian.In the idealized world of academic datasets, language is pristine. In the messy reality of user-generated content, language is noisy. Misspellings, grammatical inconsistencies, and code-switching act as friction that degrades downstream tasks like Sentiment Analysis, Named Entity Recognition (NER), and Semantic Search.

Most modern NLP stacks treat Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging and Spell Correction as isolated islands. This project stems from the realization that they are deeply symbiotic: syntax informs spelling, and spelling clarifies syntax. This post outlines the end-to-end architecture of a unified multilingual pipeline designed to clean and label noisy text, benchmarking classical probabilistic methods against modern deep learning approaches.

1.High-Level System Architecture

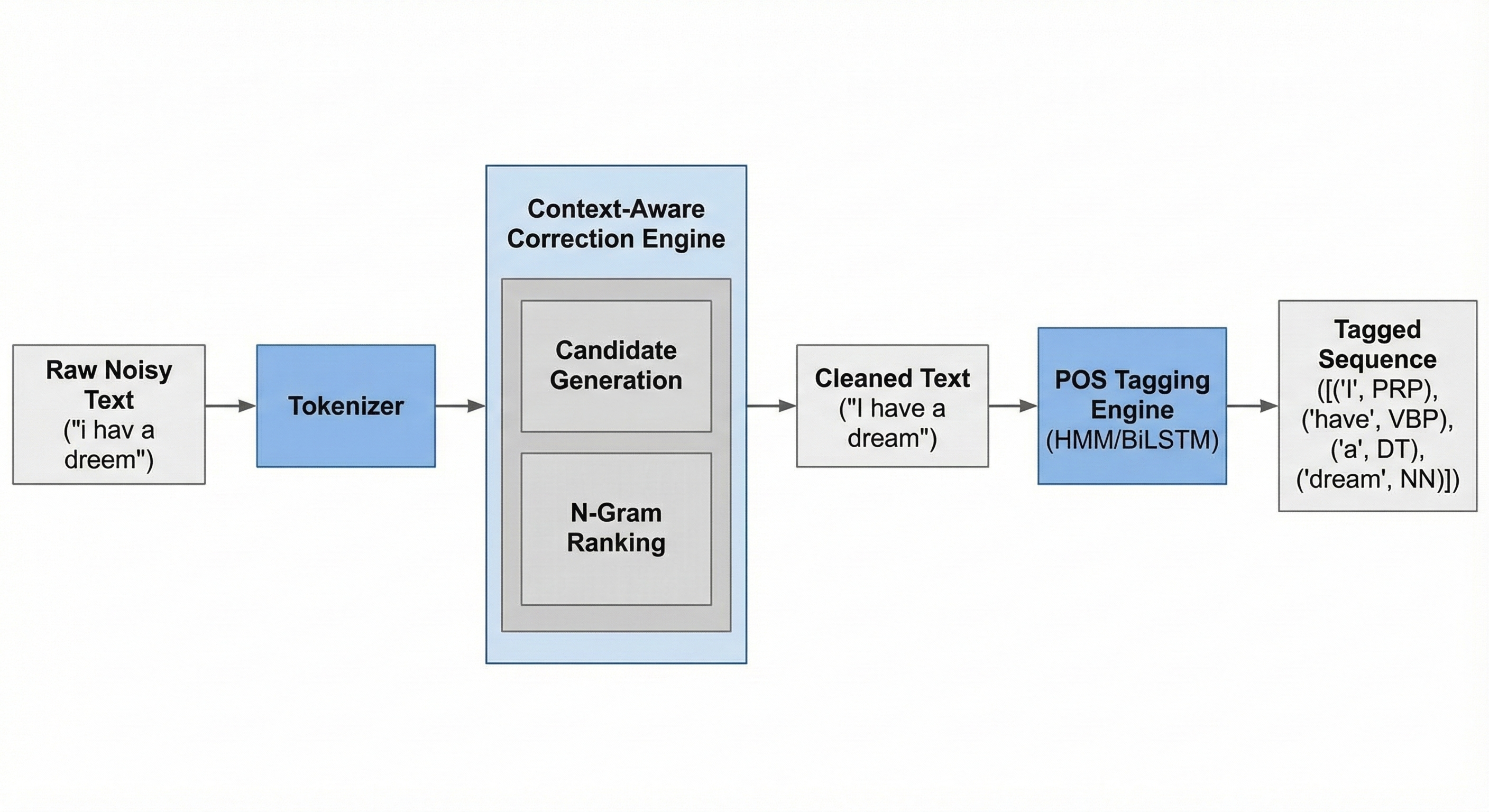

The system is designed as a sequential pipeline comprised of two primary engines: a Context-Aware Correction Engine and a Sequence Labeling Engine.

The core challenge is that an error in one module propagates to the next. If the autocorrect changes a valid noun to a verb incorrectly, the POS tagger will fail. Therefore, the architecture emphasizes joint probability and contextual awareness over isolated dictionary lookups. The Data Flow Pipeline Below is the architectural blueprint of how a raw, noisy sentence travels through the system to become structured data.

Figure 1 — Data Flow NLP pipeline

Figure 1 — Data Flow NLP pipeline

As shown above, the pipeline takes in noisy text, tokenizes it for the target language, corrects spelling errors based on context, and finally applies POS tags to the cleaned sequence.

2.Engine 1: Context-Aware Autocorrection

Standard spell-checkers often fail because they lack context—changing a valid but rare word into a common one. We implemented a probabilistic approach based on the Noisy Channel Model.

We assume the user intended to write a correct sentence S, but it passed through a “noisy channel” (their brain/fingers) and emerged as the observed noisy sentence O. Our goal is to recover the most likely original sentence

Using Bayes’ theorem, this is proportional to:

The Components

Error Model P(O∣S) (Edit Distance): We calculate the Damerau-Levenshtein distance, modeling probabilities for insertions, deletions, substitutions, and transpositions.

Language Model (N-Grams): We use trigram models with Kneser-Ney smoothing to determine the prior probability of a sequence. This allows the system to distinguish between “their,” “there,” and “they’re” based purely on surrounding syntax.

3.Engine 2: Sequence Labeling (POS Tagging)

Once the text is cleaned, the second engine assigns grammatical roles. We benchmarked two fundamentally different paradigms to understand their trade-offs in data-constrained scenarios.

Paradigm A: The Probabilistic Approach (HMM)

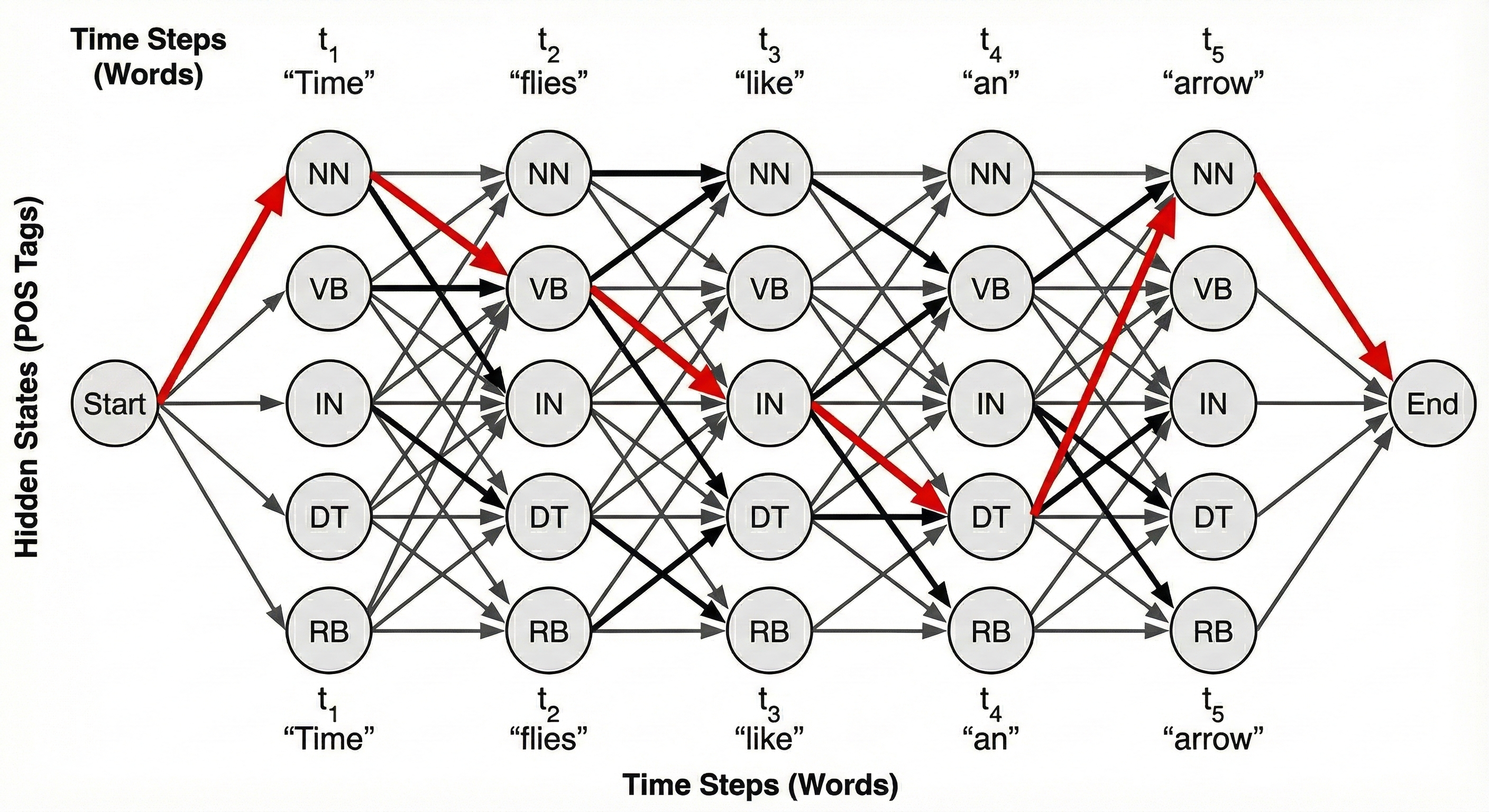

The Hidden Markov Model treats POS tags as unobservable “hidden states” that emit observable words. The goal is to decode the most likely sequence of hidden states.

We utilized a Trigram HMM decoded via the Viterbi Algorithm. The Viterbi algorithm is a dynamic programming method that finds the optimal “path” through a trellis of possible tag sequences by maximizing joint probability at every step.

Figure 2 — Trigram HMM decoded via the Viterbi Algorithm

Figure 2 — Trigram HMM decoded via the Viterbi Algorithm

The diagram above illustrates the Viterbi trellis for the sentence “Time flies like an arrow.” The highlighted red path shows the most probable sequence of hidden tags, correctly disambiguating “flies” as a verb (VB) and “like” as a preposition (IN).

Paradigm B: The Neural Approach (BiLSTM)

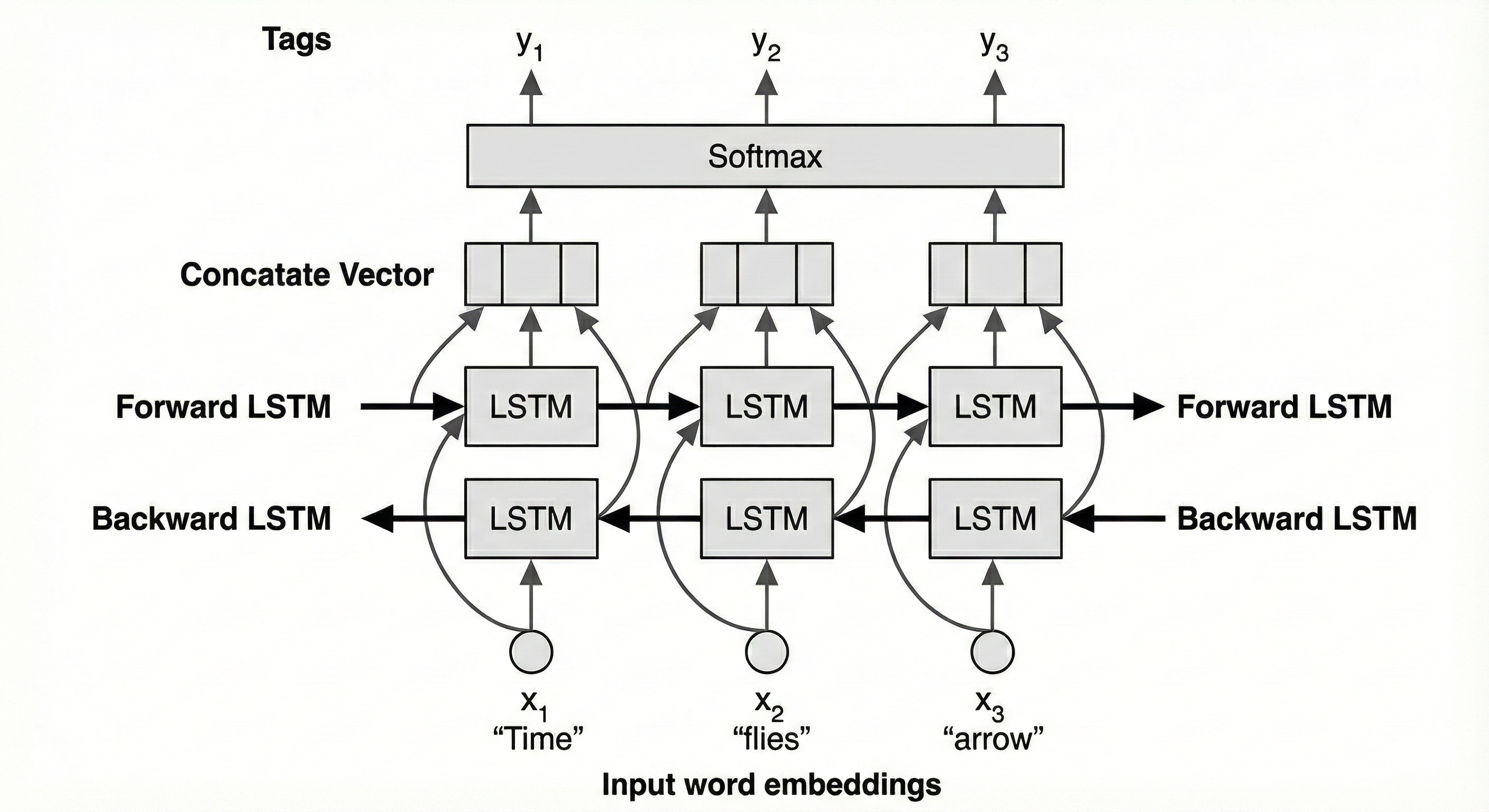

We implemented Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks. Unlike standard RNNs which struggle with vanishing gradients over long sequences, LSTMs maintain a memory cell state.

Crucially, the Bidirectional aspect processes the sequence in both directions simultaneously. To tag a word at index i, the network utilizes context from words 0…i−1 (forward pass) and words i+1…N (backward pass).

Figure 3— BiLSTM architecture

Figure 3— BiLSTM architecture

Our BiLSTM architecture, shown above, takes input word embeddings and processes them through two separate LSTM layers flowing in opposite directions. The outputs from both directions are concatenated at each time step and passed through a Softmax layer to determine the final tag probability.

4. Experimental Results & The “Small Data” Insight

We evaluated the models on gold-standard linguistic corpora across three typologically diverse languages using strict Error Rate by Word (ERW) metrics.

| Model Architecture | English ERW (~40k) | Japanese ERW (~17k) | Bulgarian ERW (~13k) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bigram HMM | 0.054 | 0.062 | 0.115 |

| Trigram HMM | 0.049 | 0.063 | 0.110 |

| Vanilla RNN | 0.295 | 0.105 | 0.572 |

| LSTM | 0.291 | 0.117 | 0.575 |

| BiLSTM | 0.283 | 0.103 | 0.558 |

Analysis: Why did Deep Learning Fail?

The results provided a critical engineering insight: Neural complexity is a liability when data is scarce.

-

Overfitting: The BiLSTM models, despite regularization, rapidly overfit the small training sets, memorizing examples rather than learning generalized grammatical rules.

-

Morphological Richness: Bulgarian, a Slavic language with complex inflectional morphology, was disastrous for the neural models. They struggled to map rare word-endings to tags without vast amounts of examples.

-

The HMM Advantage : HMMs have strong inductive biases about sequential structure built into their mathematical framework. They don’t need to “learn” that sequences exist; they assume it. On small datasets, these strong priors trump the flexible feature-learning of neural nets.

5.Final Takeaway for Production Systems

In the era of Large Language Models, this project serves as a vital reminder that architectural choices must be dictated by data constraints, not hype.

By combining the interpretability and small-data efficiency of HMMs with the contextual awareness of smoothed n-gram language models, we built a pipeline that is not just multilingual, but sufficiently robust and lightweight for real-world edge deployment scenarios where massive GPUs are unavailable.